45 Years Ago: ‘Saturday Night Live’ Makes ‘Lackluster’ Debut

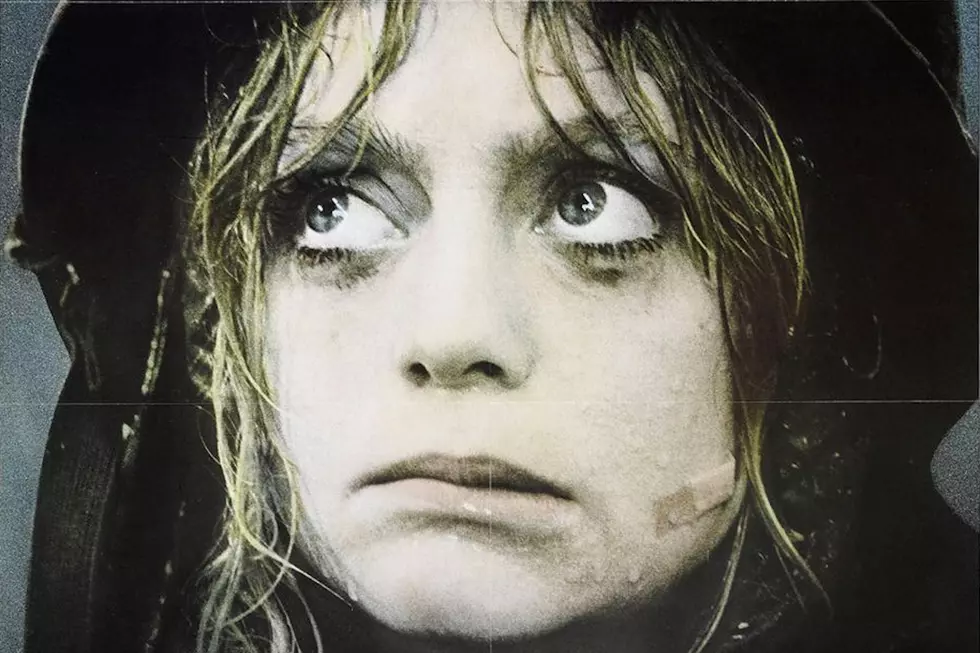

On Oct. 11, 1975 Saturday Night Live debuted on NBC. The first, largely uneven episode offered very little hint that the series would go on to become one of the most important programs in comedy history.

Saturday Night Live - originally called NBC’s Saturday Night due to the pre-existing ABC variety show Saturday Night Live With Howard Cosell - was the brainchild of Lorne Michaels. The Canadian producer teamed with NBC executive Dick Ebersol to bring the program to life.

“I would go to the Chateau Marmont [hotel in Hollywood], where Lorne lived,” Ebersol recalled in the book Live From New York: The Complete, Uncensored History of Saturday Night Live. “We worked out a loose thing of what this show is going to be. It’s going to be a repertory company of seven, and a writing staff and fake commercials and all that.”

Michaels hoped the show could disrupt the American comedy landscape, similar to Monty Python’s effect in the U.K. several years prior.

“So much of what Saturday Night Live wanted to be, or what I wanted it to be when it began, was cool,” the producer explained. “This was taking the sensibilities that were in music, stage and the movies and bringing them to television.”

Michaels recruited a collection of young comedians to make up his original cast, including John Belushi, Jane Curtin, Gilda Radner, Dan Aykroyd and Chevy Chase.

In hindsight, the premiere featured many foundational characteristics which would become synonymous with SNL’s structure. There was the “Live from New York” intro, the host’s monologue and the satirical "Weekend Update" segment. The show’s first cold open, the sketch delivered prior to the opening credits, was a scene with Belushi and Michael O'Donoghue titled “The Wolverines.”

“It seemed to me that, whatever else happened, there would never have been anything else like this on television,” Michaels recalled of the sketch, which featured Belushi as an immigrant learning English, only to have his teacher keel over after a sudden heart attack. “No one would know what kind of show this was from seeing that.”

Despite having some structural similarities to its future form, much of the debut SNL episode was far different than the show’s later incarnation.

The first host, George Carlin, did not appear in any of the evening sketches. Instead, the iconic comedian delivered the opening monologue and three different stand-up sets. The show featured two different musical guests -- Billy Preston and Janis Ian -- each performing two songs.

Special guests who were not part of the cast, namely Andy Kaufman and Valri Bromfield, were given solo time to perform their unique comedy acts. Kaufman delivered his famous Mighty Mouse routine, while Bromfield imitated a high school teacher and volleyball player during her time.

Elsewhere in the show, “The Impossible Truth,” a short film by Albert Brooks, offered a satirical look at fake news stories. The comedian had been invited to become a member of SNL’s cast, but was hesitant because he “didn’t want to do television.” Instead, he crafted short prerecorded vignettes which would air throughout the first season.

Then there were the Muppets. Yes, early on the Muppets were part of SNL’s lineup. These were not the Kermit and Big Bird characters that young audiences had already embraced, but rather a new series of characters designed for a more mature crowd. King Ploobis, Queen Peuta, their son Wiss, and servants Scred and Vazh would appear in the first of a recurring segment called “The Land of Gorch.” These Jim Henson creations made references to everything from sex to drugs and alcohol. They also weren’t very funny.

“Whoever drew the short straw that week had to write the Muppet sketch,” writer Alan Zweibel remembered, revealing that the show’s staff largely hated their plush coworkers. The writer also recalled watching O’Donoghue hang a stuffed animal of Big Bird from the office blinds. “He was lynching Big Bird. And that’s how we all felt about the Muppets.”

Still, “The Land of Gorch” was emblematic of SNL’s initial overall approach. In their determination to be different, Michaels and his team used a “see what sticks” technique, throwing a wild variety of ideas into the first episode, hoping something might pop.

To that end, the show’s cast members, dubbed the Not Ready for Prime-Time Players, had only a fractional stake in the debut show. With the musical performances, guest appearances, Carlin’s stand-up and the other aforementioned segments, only five true sketches were featured in the first episode, a ratio that was more reflective of other variety shows at the time. The skits, along with five fake commercials, were the cast members’ main source of screen time.

“There were only four or five sketches,” Ebersol recalled. “If you go back and look at the first show on the air, the two people by far who had the most to do were Chevy and Jane.”

Few, if any, of the sketches earned big laughs from the studio audience. Yes, the previously mentioned “Wolverines” went well enough, but “Bee Hospital” and “Trial” were duds, while most of the fake ads were simply forgettable, save for the three-blade razor ad which turned out to be quite prophetic.

Reviews of the first episode were harsh. The Hollywood Reporter said the show “got off to a less than auspicious start,” calling the debut “lackluster” and decrying its “lack of exciting guests and innovative writing.” New York described it as “an uneven show, with all of the pitfalls and possibilities of something never tried before,” but added it was “rooting for” the program to succeed.

Of course, by now we all know that it did succeed. Saturday Night Live went on to become one of the most successful programs in TV history, launching countless careers, earning 73 Emmys and lasting on television for 45 years (and counting). Still, the majority of those achievements seem unfathomable when watching the first episode -- proof that the show's legacy was paved far more by where it went than how it started.

Rock's 60 Biggest 'Saturday Night Live Moments'

More From 92.9 NiN